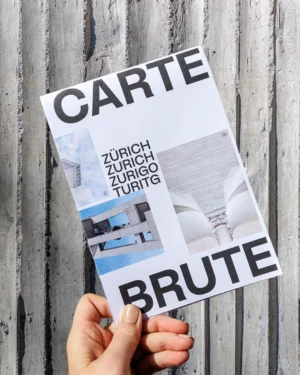

Unteraffoltern II

- Residential

- Georges-Pierre Dubois

- 1967-1970

- Frohnwaldstrasse 94, Im Isengrind 35, 8046 Zurich

- Zürich

- Award for Good Buildings, City of Zurich, 1972

- Listed in Carte Brute Zurich

Words & images: Karin Bürki

Here’s an idea for an urban walk. It takes you from the busy Oerlikon district in the north of Zurich along quiet fields, past a farm, through a forest and ends in a carefully manicured park. Take a seat at one of the wooden picnic tables, sink your lips into your sandwich and admire the breathtaking view of the two Le Corbusier-style Unteraffaltern II concrete tower blocks.

Yes, these two 40-metre-high and 63-metre-long brutalist structures are absolutely worth a visit. Here’s why and what makes them important.

From Marseille to Zurich

The brutalist architecture reflects the optimistic, concrete-loving spirit of the boom years. The seminal apartment block Unité d’habitation in Marseille, designed by the Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier in 1952, served as a blueprint. Trademark features include exposed concrete, stacked and vertically nested duplexes, communal areas and integrated shops. The Unités were intended to be surrounded by well-maintained green spaces. Zurich’s response came from someone who knew his job: Georges-Pierre Dubois had worked in Le Corbusier’s Paris office in the 1930s and built the first Swiss Unité in Arbon in canton of Thurgau, in 1960.

The Dubois Unités boast an ingenious flat structure, light-filled duplexes and spacious communal areas. A unique feature is the lavish entrance halls, which contain lush mini botanical gardens complete with water features. The mailboxes come in bright yellow, green, blue and orange. The whole thing is so inviting, even the indoor picnic table makes sense.

Here’s another reason why the blocks matter:

Unteraffoltern II was the centrepiece of one of the city’s largest postwar developments. The housing estate accounted for a third of the more than 700 new flats for 5000 people the city began building in the 1960s to tackle the need for new, affordable housing.

In the late 1990s, the two towers underwent a major refurbishment. The facades were updated and wheelchair ramps was added to the entrance halls. Changing housing needs and a desire for a more diverse tenant mix led to a third of the 264 flats being combined into larger units between 2002 and 2003. Each building now comprises 118 flats, ranging from one to five-and-a half bedrooms and accommodating up to 250 people.